The rise of the Sportister: Football, fashion, and the new global code

Football, fashion and culture converge like never before

Once a staple of pub signage across the UK, a warning against trouble disguised in polyester. Football shirts, track tops, branded trainers, coded signals of tribal allegiance, of potential violence, of places not safe for everyone.

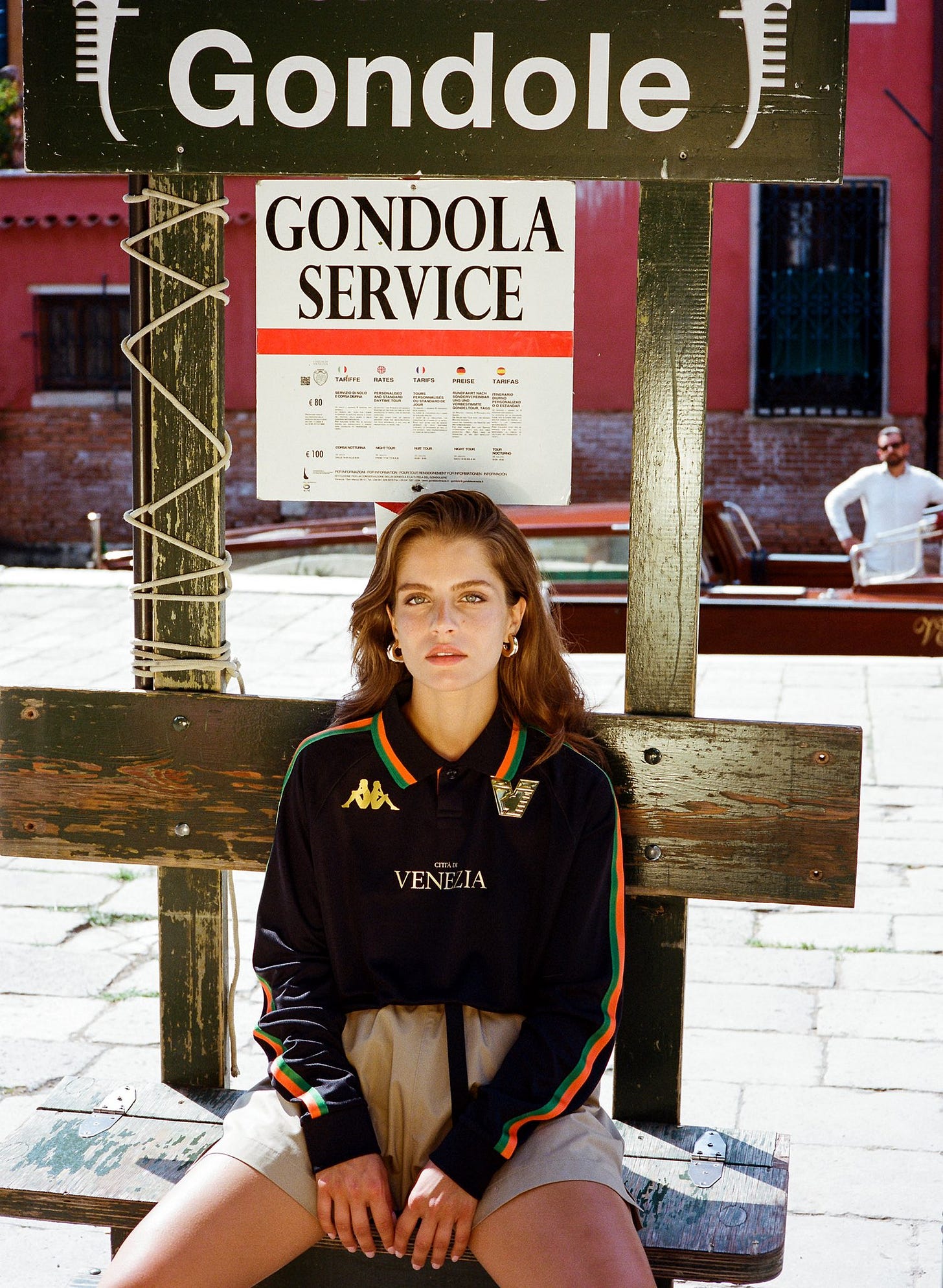

Today, those same garments feature on Paris runways, in Tokyo lookbooks, and across the street scenes of New York, Lagos and Melbourne. Something has changed. The silhouette of football has shifted. A new aesthetic has emerged, the Sportister.

The Sportister is not a person. It is a movement. A cultural tendency. A global remix of sportwear, memory and styling. It draws loosely from hipster aesthetics and football culture, but cannot be reduced to either. It is genderless, class-fluid, globally fluent. And crucially, it speaks in visual codes that were once dismissed or policed, now celebrated, commodified and reframed.

At its core, the Sportister movement reclaims and repositions garments that were once either aggressively masculine or culturally marginal. Football kits, vintage track tops, nylon runners, and club scarves worn like silk accessories, these pieces no longer signal exclusion. They now signify culture.

A Global Soft Power Turn

This is more than fashion. It is cultural memory woven into cotton. Where football kits were once worn in closed tribal circles, now they travel, through cities, through genres, through style cultures that don’t care who won the league in 1994.

From Seoul to São Paulo, Paris to Melbourne, retro kits and training wear are now part of a broader visual grammar. Vintage Inter Milan shirts styled with pleated trousers in Shibuya. Balenciaga riffing on shin guards and boot silhouettes. Jackson Irvine footballer, musician, adidas collaborator, quietly curating a lookbook of subcultural style and social conscience.

This is a form of soft power, not the state-sponsored kind, but something fan-forged and culturally mobile. The Sportister aesthetic is subtle and layered. It blends football memory with fashion fluency, creating new ways of seeing, and being seen.

From Subculture to Style Culture

Football has always had fashion codes. The casuals. The paninari. The mid-2000s grime-era match shirts under puffers. But these were historically local, closed, often masculinised. The Sportister breaks from this logic. It does not dress to intimidate or exclude, it dresses to translate.

Where once kits and tracksuits were seen as aggressive, class-marked, or juvenile, they are now reframed as design artefacts. The 1990 West Germany shirt is no longer just an item of fan nostalgia, it is a cultural product with global relevance. The ’94 Nigeria shirt. The Juventus Kappa years. Even forgotten away kits from 2003, all reappear, now worn with intention, recontextualised through fashion editorials and curated drops.

This is not about retro fetishism or casual cosplay. It is about reactivating football’s visual heritage in a new cultural economy, one where meaning circulates through aesthetics.

Entertainment in Layers

Football is no longer just a game, it is a format. A platform. A narrative engine. And in this world, what players wear, what fans wear, what musicians wear, it all blurs.

Clubs now collaborate with musicians and fashion designers. Kits are launched as capsules. Jerseys are worn on stage, in videos, on catwalks, in places where the ball never rolls. The Sportister movement flows through this convergence, where music, football, and memory weave into a single cultural current.

And this matters. Because in a media-saturated world, what people wear becomes part of how they speak. The Sportister is not just a fashion development, it is a sign that football culture has moved from the margins to the centre of global style. It is a wearable archive. A style that remembers.

Commerce in Kit Form

The rise of the Sportister is not just a style shift, it has global economic consequences. As football moves further into the realms of fashion, entertainment and digital storytelling, its products no longer belong solely to the sporting domain. Shirts are no longer merchandise; they are cultural capital. Drop culture, resale markets, capsule collections, collaborations with designers and musicians, all now form part of football’s expanding symbolic economy.

This has commercial power. But it also raises questions. Who owns football’s visual heritage? Who profits from its global recontextualisation? As kits from the 1980s and 1990s become collector’s items, as brands reissue icons and remix subcultural signals, the aesthetic memory of football is being monetised, not always by those who lived it first.

And so, the Sportister movement, while celebratory and creative, also reveals something deeper about contemporary globalisation. Football has become one of the most powerful engines of cultural consumption in the world, soft power worn on the street, sold in limited runs, and endlessly reshared. It is both beautifully democratic and structurally uneven.

The game has always sold moments. Now it sells experiences, memories and style.

Footnote

The above image was sourced from https://x.com/VeneziaFC_EN/status/1545074076116553730/photo/1